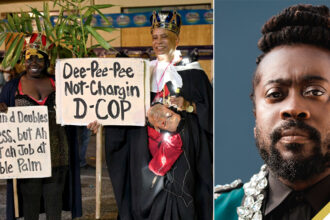

“Jamaica’s carnival has caused a lot of ruckus. It’s caused a lot of ruckus because it is not being done correctly, and if we want to stop the fussing, Jamaica Carnival has two choices right now.” With this pointed declaration, Caribbean cultural and social media commentator Babbzy has set off a firestorm across the region, reigniting fierce debates over authenticity, ownership, and the evolving identity of Carnival in the Caribbean. Her criticism centers on Jamaica’s growing integration of dancehall music into its Carnival celebrations—an approach she believes disrespects the festival’s soca-driven roots and erodes its historical significance.

The critique comes on the heels of a recent Jamaica Observer article titled “Carnival Capital of Caribbean? Jamaica Takes Aim at Title,” which detailed the island’s rapid growth in Carnival tourism. In 2025, Jamaica welcomed 16,958 visitors during the Carnival week and last year raked in approximately JMD $4.42 billion (USD $28.6 million) in direct revenue. Broader economic impact estimates topped JMD $95.4 billion (USD $618 million), underscoring the festival’s rising influence. Tourism Minister Edmund Bartlett hailed the event’s success, noting a 20% uptick in arrivals and massive participation from the Jamaican diaspora in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K.

But while the economic wins are undeniable, critics like Babbzy argue that Jamaica’s Carnival lacks the cultural depth seen in Trinidad and Tobago—the undisputed epicenter of Caribbean Carnival. “Carnival is about soca, steelpan, calypso, and masquerade. It was born out of struggle and emancipation,” One commenter explained. Trinidad’s Carnival, with roots going back to the 18th century, generates over TT$1 billion (USD $147 million) annually and welcomes upwards of 40,000 visitors each year. Its structure includes hallmark events such as Panorama, the Calypso Monarch, and Soca Monarch—integral traditions that celebrate the region’s rich cultural legacy.

Jamaica’s modern Carnival, revived in the 1990s by Byron Lee, was initially a tribute to soca and Caribbean unity. However, as dancehall becomes more prominent in parades and parties, purists worry that the island is shifting the festival’s core. “This is not about excluding Jamaica,” said a Trinidadian bandleader. “But if you want to host Carnival, it must reflect what Carnival actually is. Otherwise, it becomes something else entirely.” The concern, many say, is not about competition—but about cultural preservation.

As Jamaica continues to rise as a Carnival destination, it faces a cultural crossroads. Will it redefine the Caribbean festival experience on its own terms, or will it honour the foundation built by its regional neighbours? For now, the music plays on—but the region is listening closely to every note.

View this post on Instagram